Polypharmacy/Multiple Drug Classes

| Type | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| When to deprescribe | |

| CBR |

Given the potential clinical and economic benefits in reducing inappropriate polypharmacy, we suggest that in addition to applying a targeted approach to deprescribe specific drug classes, regular medication review is offered to older people taking multiple long-term medicines. We suggest deprescribing medicines that meet one of the categories below:

|

| GPS |

Deprescribing decisions should be made in consultation with the person and their GP and/or specialist providers to ensure it aligns with their preferences, goals and overall treatment plans (ungraded good practice statement). |

| GPS |

In the context of multimorbidity and polypharmacy, healthcare providers should refer to existing high-quality, disease-specific guidelines relevant to the condition to identify medicines that may be suitable for deprescribing (ungraded good practice statement). |

| GPS |

Deprescribing should be a preference-sensitive decision, requiring a shared decision-making approach (ungraded good practice statement). |

| Ongoing treatment | |

| CBR |

We suggest continuing medicines after confirming that the pharmacotherapy is clearly indicated, the benefits of the medicine are expected to outweigh the potential harms and that this aligns with the individual's goals and preferences. In the context of multimorbidity and polypharmacy, deprescribing one medicine may necessitate a change in other pharmacotherapies due to a potential increase or reduction in risks (e.g. drug-drug or drug-disease interactions). There may be a need for a “deprescribing cascade” or prescribing of another more suitable medicine to optimise therapy. |

| How to deprescribe | |

| CBR |

Methods When a medicine is identified as being suitable for deprescribing, we suggest developing an individualised deprescribing plan in collaboration with the person and/or their carers/family members, by referring to the specific guidance in individual drug sections in this guideline. Broadly, for medicines where adverse drug withdrawal events (ADWEs) or disease recurrence are likely, we suggest tapering the dose rather than abrupt cessation. For tapering,* we suggest halving the dose at two to four weeks intervals, until half of the lowest standard dose formulation is reached, then ceasing the medicine completely. However, smaller dose reductions may be appropriate (e.g. high baseline dose or high risk of symptom recurrence). We suggest switching from regular doses to pro re nata doses be considered if appropriate (e.g. antipsychotics). For medicines with longer half-lives, we suggest tapering may not be required. We suggest deprescribing one medicine at a time. However, up to three medicines may be deprescribed simultaneously if unlikely to cause ADWEs and practical, or if withdrawal effects can be clearly attributed to an individual medicine. If deprescribing cannot be fully implemented and/or maintained, we suggest the following options be considered and offered to the individual as appropriate:

* When deprescribing fixed-dose combinations, if tapering of one active component is required, consider prescribing separate (i.e. free-dose) combination products. |

| CBR |

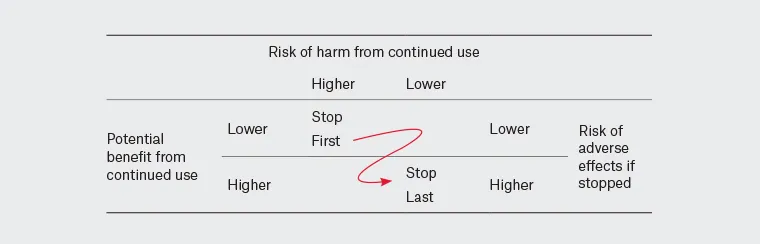

Sequence of deprescribing target medicines Once the medicines for deprescribing are agreed upon, we suggest the order of deprescribing be decided collaboratively between the individual and their prescriber. We suggest considering the priorities of the person, including their preference and impact on well-being, alongside the characteristics of the medicines, taking into account the balance of potential:

Image reproduced from: Quek HW et al. Aust J Gen Pract. 2023 Apr;52(4):173-180. Footnote: Consider the individual's priorities, including their preferences and the impact on their well-being, alongside the characteristics and cost of the medicines |

| GPS |

With informed consent from the individual or their supported decision-maker, prescribers should provide written prescribing and deprescribing plans to relevant healthcare providers involved in the person’s care (ungraded good practice statement). |

| GPS |

Prescribers should document informed consent, the rationale for prescribing or deprescribing, and, if applicable, the dose tapering schedule, order of withdrawal, and monitoring plan (ungraded good practice statement). |

| Monitoring | |

| CBR |

In general, we suggest closely monitoring for ADWEs and any health-related outcomes (e.g. physical/psychological changes) every two weeks following each dose adjustment until at least four weeks after the medicine is fully discontinued. After this initial period, we suggest monthly monitoring for at least three months, followed by monitoring every six months thereafter. If in-person visits are not practical, we suggest informing people to report symptom recurrence and/or any appearance of new symptoms during monitoring and setting parameters for people for which point to initiate contact. We suggest individualising monitoring intervals (more or less frequent) in partnership with the person and their carers based on practicality, individual preferences, responses and tolerance. For instance, deprescribing multivitamins taken without a current indication in a robust person may require less frequent monitoring than other drug classes such as an antihypertensive or an antipsychotic. For specific guidance, we suggest referring to the individual drug sections in the guideline. Additionally, we suggest monitoring should occur at any time there is a change in the individual's risk-benefit profile (e.g. if the person becomes unwell or there is a change in their clinical status or preferences). |

CBR, consensus-based recommendation; GPS, good practice statement

As discussed earlier in the introduction and summaries, medicine optimisation is one of the integral parts of the healthcare of older people. Medicines are prescribed to manage symptoms or prevent disease-related outcomes. As people age, they are more likely to develop diseases resulting in the use of more medicines. The concurrent use of multiple medicines is commonly referred to as polypharmacy [4].

As shown in Table 5, deprescribing to reduce polypharmacy or multiple drug classes was not found to have a significant impact on mortality in randomised controlled trials (odds ratio, OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87, 1.08; studies = 25; participants = 15,374; low certainty) and non-randomised studies (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.36, 1.38; studies = 6; participants = 853; very low certainty). The deprescribing group had significantly increased adverse drug withdrawal effects (ADWEs) (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.48, 2.66; studies = 4; participants =3096; low certainty) compared to the continuation group. ADWE is referred to as a clinically significant set of signs or symptoms caused by the discontinuation of a drug [112].

There was no statistically significant difference between deprescribing and continuation groups in the following outcomes:

- Exacerbation of underlying conditions (OR 6.75, 95% CI 0.33, 136.91; study = 1; participants = 58; very low certainty)

- Falls (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.66, 1.17; studies = 11; participants = 8416; very low certainty)

- Fractures (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.60, 1.57; studies = 5; participants = 4867; low certainty)

- Adverse drug events (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.64, 1.91; studies = 3; participants = 5492; very low certainty)

- Emergency department presentations (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72, 1.01; studies = 6; participants = 4287; low certainty)

- Unplanned hospital admissions (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.82, 1.21; studies = 13; participants = 11,157; low certainty).

In one study involving deprescribing potentially inappropriate polypharmacy, a significantly smaller proportion of participants in the intervention group reported worsening anxiety or depression at follow-up (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15, 0.93, n = 137). Deprescribing did not lead to a significant difference in cognition and quality of life in most studies measured using standardised measures.

Overall, there is a paucity of direct evidence indicating significant harms or benefits associated with the general deprescribing targeting multiple medicines. The certainty of evidence is low and very low. There is also a wide variation in the reported person-oriented outcomes such as morbidity, physical function, cognitive function, and quality of life. The substantial healthcare expenditure associated with inappropriate medicine use and the broad applicability of deprescribing intervention in different healthcare settings provided the basis for formulating consensus-based recommendations in the absence of quality evidence.

For more information relating to the certainty of evidence for each outcome, please refer to the Technical Report.

Various methods were used for deprescribing in the included studies due to different targeted medicines and there was no direct evidence that any particular method was associated with the greatest benefits and harms. However, compared to abrupt cessation, dose tapering is likely more acceptable for most people and practical to determine the lowest effective dose for some people requiring dose reduction rather than complete cessation.