Executive Summary

Deprescribing is a person-centred process of medication withdrawal intended to achieve improved health outcomes through discontinuation of one or more medications that are either potentially harmful or no longer required. The process is undertaken as a partnership between the consumer and their healthcare provider.

The aim of this guideline is to bridge the gap from deprescribing research to practice by translating research evidence into recommendations that are actionable, acceptable, feasible, and implementable in care practice for older people. Clinical practice guidelines for deprescribing exist for key drug classes. Our goal is to provide broad guidance for deprescribing medicines, that complements more detailed drug-specific deprescribing guidance, disease-specific therapeutic guidelines, and non-pharmacological management resources. The current guideline aims to provide a summary of recommendations for when, how, and for whom deprescribing may be considered and offered, with a shared decision-making process involving individuals, their family members, carers, or support persons to ensure decisions align with individual health goals, values, and preferences. Like any healthcare intervention, deprescribing is not without potential risks. This guideline aims to identify monitoring requirements during the deprescribing process and address ongoing treatment needs as applicable. Although this guideline has been developed with a focus on medicines commonly used by older people in Australia, the guideline draws on evidence from studies conducted globally. We anticipate that this guideline will have international relevance. However, variations in medicine availability, regulatory frameworks and clinical practices may necessitate adaptations to align with country-specific treatment guidelines.

Through the implementation of this guideline, it is anticipated that inappropriate or unnecessary medicine use will be reduced and avoidable medicine-related harm prevented. Additionally, by minimising pharmaceutical waste, the guideline may help reduce the environmental impact of medicines, support a more sustainable healthcare system, and promote the rational and responsible use of medicines.

The current clinical practice guideline ("guideline") aims to provide a resource for healthcare providers to guide the deprescribing of commonly encountered medicines in routine clinical care. It provides information to support healthcare providers in determining whether deprescribing is appropriate for specific drug classes as well as including overarching information for deprescribing in the context of polypharmacy or multiple drug classes. It provides a summary of recommendations for when, how and for whom deprescribing may be considered and offered, with a shared decision-making process involving individuals, their family members, carers, or support persons to ensure decisions align with individual health goals, values, and preferences. Additionally, this guideline aims to identify monitoring requirements during the deprescribing process and address ongoing treatment needs as applicable.

The target audience for the guideline is health practitioners involved in the care of older people, particularly medical practitioners, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and other non-medical prescribers such as dental practitioners, podiatrists, and optometrists, all of whom may be involved in the shared decision-making for deprescribing. This guideline is applicable in the various settings where deprescribing decisions may be made including primary care, hospitals, and residential care. It is intended as a practical guidance to help prescribers decide with the individual which regular medicines can be considered for deprescribing.

This guideline relates to deprescribing in older people. Older people are generally defined as those aged 65 years and over (see Glossary of Terms) [1]. Evidence informing this guideline is based on studies involving participants aged ≥ 65 years taking at least one regular medicine (see Technical Report “7. Part B: Systematic Evidence Review”). While the guideline focuses on this population, some recommendations may apply to others, as chronological age does not always reflect health status. In particular, individuals aged 50 years and over are considered older among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Clinical judgment should be applied with care when interpreting and applying these recommendations to people outside the intended scope.

This guideline does not address all medicines available in the market. It focuses on the top 100 commonly dispensed medicines in the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for people over 65 years. The GDG reviewed and considered the inclusion of less commonly used medicines (not part of the top 100) where evidence for deprescribing is identified in the literature search. A limitation of using the PBS data to estimate common medicines is the data does not include medicines available without a prescription, such as over‐the‐counter and complementary medicines, or medicines dispensed on private prescriptions. While these medicines are not addressed in the guideline, optimising the overall treatment regimen, including non-pharmacological therapy, remains equally important and aligns with the National Medicines Policy’s Quality Use of Medicines framework and best practice [2].

The guideline includes only medicines prescribed for regular use. Medicines prescribed for pro re nata (as needed) use in acute exacerbations (e.g. salbutamol or glyceryl trinitrate) or for short-term treatment of acute illnesses such as infections (e.g. amoxicillin) were excluded. Medications or formulations not commonly administered in the setting of chronic disease management in older people (e.g. contraceptives) were also excluded. Where recommendations involve tapering a dose, healthcare professionals are advised to consult relevant resources and available medicine information to determine the most appropriate method for dose adjustment based on the medicine, its formulation, and person-specific factors. This guideline is not intended to be used as a substitute for disease-specific therapeutic guidelines and evidence-based resources related to non-pharmacological strategies for the management of a medical condition.

Under-prescribing is another important aspect of medicine management which occurs when a clinically indicated medicine is not being prescribed for a person. This guideline does not consider appropriate medicines that are not present, or omissions, as this is beyond the scope of this deprescribing guideline. It is likely that, in some cases, clinically indicated medicines may be identified during the deprescribing process. The information provided in this guideline should be considered in the context of an individual's circumstances (including health and financial status), life experience, goals and expectations as well as cultural and personal values and beliefs.

The scope of this guideline will be reviewed and revised as appropriate in future updates, in line with best practice, to ensure it remains relevant, inclusive, and responsive to emerging evidence and stakeholder feedback.

There are two main parts to this guideline. The first section, Polypharmacy/Multiple Drug Classes, can be viewed as the general principles for deprescribing. This section includes evidence on deprescribing without specifically targeting specific drug classes which includes studies targeting polypharmacy, three or more drug classes, or medicines with a pharmacological action covering multiple drug classes (e.g. anticholinergic and sedative medicines, fall-risk increasing medicines, and psychotropic medicines). Subsequent sections are organised by specific drug classes. Within each section, individual medicines or drug classes are discussed.

Deprescribing is inherently intertwined with and an essential part of good prescribing practice. In each specific drug class section of this guideline, a brief review of relevant guidance for the appropriate use and continuation of medicines is provided. This review is not based on a systematic literature review but incorporates evidence from a non-systematic review of sources including clinical practice guidelines, position statements, and expert consensus documents.

Further details on the recommendation types can be found in the Methodology section. The Summary of Recommendations provides a brief overview, serving as a quick reference to support clinical decision-making. For more information on the evidence review process, refer to the individual drug class sections in the appendices of the Technical Report. The Technical Report documents the methodology, evidence synthesis, and decision-making framework supporting the recommendations, including considerations of benefit-risk balance, values and preferences, resource implications, acceptability, and feasibility.

The information and recommendations presented in this guideline represent the view of the GDG, based on careful consideration of the available evidence. It is not mandatory to apply the recommendations, and the guideline does not replace clinical judgment or the responsibility to make decisions tailored to the individual’s circumstances, in consultation with the person, their family, and/or carers. Figure 1 suggests steps to use this guideline effectively. For detailed information on each section, refer to the Guideline structure section.

Figure 1. How to use this guideline?

On 30 June 2020, one in six (approximately 4.2 million) Australians were aged 65 and over [3]. At least 250,000 hospital admissions in Australia annually are medicine-related, with the majority involving older people [3]. Two-thirds of these unplanned hospital admissions are potentially preventable [4]. The use of multiple concurrent medicines is especially prevalent among older people and is commonly referred to as polypharmacy [5]. Polypharmacy affects almost one million older Australians, and continues to rise with the number of people affected increased by 52% from 2006 to 2017 [6]. While some medicines are clinically indicated, polypharmacy in older people is associated with an increased risk of hospitalisations, functional impairment, geriatric syndromes (including confusion, falls, incontinence, and frailty), and mortality [7]. Paradoxically, polypharmacy is also associated with under-prescribing, where people may not receive indicated medications for treating or preventing a condition due to concerns about further complicating their regimen [8].

Medicines play a critical role in managing chronic conditions, curing disease, and offering symptomatic relief that can significantly improve a person’s functional capacity and quality of life. Some medicines are intended to reduce the risk for a condition rather than manage current symptoms or active disease. However, the medicines intended to improve health outcomes can also cause harm. Evidence suggests that an increasing number of medicines was associated with an increased risk of medicine-related harm [9]. The use of a medicine is typically a trade-off between benefits and risks. For people with chronic diseases, the assessment of the benefits and risks of medicines is likely to evolve throughout their disease journey depending on their treatment experience, clinical situation, and changing needs [10]. As such, appropriate monitoring is essential as a medicine that was once beneficial may become less suitable over time. These medicines are referred to as potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs) which are medicines where the risk of harm may potentially outweigh the benefits, that are used instead of a lower-risk and equally or more effective alternative or are used without an existing evidence-based indication [11, 12]. The use of PIMs is highly prevalent among older people worldwide [11, 13]. Multimorbidity and concurrent use of multiple medicines were associated with the high prevalence of PIM use [14]. The use of PIMs in older people leads to negative health outcomes, including adverse drug events [15], hospitalisations [16, 17], and high healthcare expenses [18]. Among older people with dementia, the use of PIMs significantly increased the risk of falls and fall-related injuries [19].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) Medication Without Harm initiatives highlight that unsafe medication practices and errors are a leading cause of injury and preventable harm globally, costing an estimated USD 42 billion annually [20]. In 2020, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care released Australia’s response to the challenge with goals to reduce avoidable medication errors, adverse drug events, and medication-related hospital admissions [21]. Medicine safety is a health priority for Australia’s ageing population. Over the last few years, wide-ranging reforms have been introduced to the aged care system to improve the quality of care provided to older people. Notably, in Australia, the new Aged Care Act will come into effect on 1 November 2025 [22]. This legislation includes measures to support the safe and appropriate use of medicines, including reducing the inappropriate use of high-risk medicines such as psychotropic medicines [23].

Medicine use in older people is a fine balance of managing the underlying symptoms or risks in accord with the older person’s preferences, while at the same time minimising drug-related problems through monitoring, reducing pill burden, and avoiding unnecessary medicine use. Older people are at an increased risk of adverse drug events and harm arising from potentially inappropriate medicine use and adverse drug interactions [24-28]. Adverse drug events are defined as any injuries resulting from medical intervention related to a drug [29] which includes physical harm, mental harm, or loss of function. The incidence of adverse drug events increases with the number of medicines used [30]. Adverse drug events are frequently under-recognised and can be mistaken for symptoms requiring further treatment, which leads to inappropriate prescribing cascades [31] or maybe simply dismissed as an unavoidable consequence of ageing. The reasons why older people are at an increased risk of medicine-related harm are multifactorial and include factors such as drug-drug interactions, prescribing cascades, frailty, physiological changes, and multimorbidity [32, 33]. A recent longitudinal study suggested that older people with greater frailty are more likely to experience medicine-related problems, which can, in turn, further exacerbate their frailty [34].

Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy through deprescribing aligns with international patient safety priorities. Deprescribing acknowledges that the need for medicines is dynamic as an individual's circumstances may evolve with time. It is a systematic process to optimise an individual's medication regimens with the ultimate goal of reducing harm as well as improving outcomes and quality of life [21]. Prescribing and deprescribing are two interconnected aspects of medicine management. While prescribing involves initiating medicines and deprescribing involves discontinuing or reducing the dose of a medicine, both are intended to improve health outcomes. Rational prescribing emphasises the continuous monitoring of treatment for efficacy and adverse outcomes. Existing clinical practice guidelines are largely single-disease-focused and do not reflect the reality of multimorbidity (defined as the presence of two or more chronic health conditions) in practice [35]. The management of multimorbidity is often complex. Strictly following all the recommendations in current single-disease guidelines without incorporating individual preferences and circumstances can result in an overwhelming treatment burden for older people with multimorbidity [36]. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Silver Book is a valuable resource for healthcare professionals, particularly general practitioners (GPs), caring for older people in both community and residential aged care settings [37]. It addresses the complex and unique challenges GPs encounter in aged care, including guidance on common clinical conditions, general and organisational approaches to care, and principles for deprescribing. The Silver Book also outlines a five-step approach to deprescribing in clinical practice.

Deprescribing is a person-centred process of medication withdrawal intended to achieve improved health outcomes through discontinuation of one or more medications that are either potentially harmful or no longer required. The process is undertaken as a partnership between the consumer and their healthcare provider [33]. It involves carefully evaluating whether the ongoing use of certain medicines continues to offer more benefits than risks, particularly as an individual's circumstances change. A medicine clinically indicated for an individual's condition at a specific point in time may not be appropriate or necessary in the future. As such, ongoing monitoring is important to adapt health management strategies based on their changing needs, goals, preferences, or priorities over time. Deprescribing provides an opportunity for medication reconciliation and optimising medication regimens to ensure the medicines are prescribed based on the best available evidence and aligned with the individual's goals, on the proposition that the person is likely to derive more benefit than harm.

Deprescribing is a promising intervention to reduce treatment burden [38, 39]. Studies have shown that deprescribing significantly reduced both the total number of medicines and the use of potentially inappropriate medicines among older people across various settings, including the community [40] and residential aged care facilities [41]. However, findings on the feasibility and impact of deprescribing in hospital settings remain mixed [42-44]. The impact of deprescribing is context-dependent. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nine randomised controlled trials found that reducing polypharmacy was associated with lower mortality among the young-old (aged 65–79 years) [38, 39]. The effects of deprescribing on other health-related outcomes such as falls are inconclusive [45]. It is possible that health-related outcomes are multifactorial in nature, warranting a multifactorial approach.

Deprescribing is generally well accepted by older people, with over 90% willing to stop one of their medicines if their doctor deemed it appropriate [30]. However, deprescribing in clinical practice is a challenging process [46], and health professionals consistently cite the scarcity of synthesised evidence or guidance as a barrier to deprescribing [30]. Deprescribing is not a decision made in isolation but requires careful consideration of various individual factors, including overall health, quality of life, goals, preferences, affordability, pill burden, health literacy, and adherence to the current medication regimen [47]. In addition to the clinical benefit-harm profile, consideration of financial implications is essential to delivering person-centred care. Affordability of care can influence how individuals weigh the benefits and risks of medications, especially when the evidence on those benefits and risks is uncertain [48].

Existing resources that support health professionals in identifying potential target medicines for deprescribing include lists of high-risk medicines and decision aids [47]. Lists that identify high-risk medicines in older people can prompt prescribers to re-consider these potentially high-risk medicines. These explicit lists do not require specialist in-depth knowledge; however, they are general in nature and do not provide specific advice or information on how to withdraw identified medicines in an individual and how to monitor the process of medicine withdrawal [49]. Most of these lists also do not suggest safer alternative treatments or therapies. In addition to this, implicit tools are also available such as the Good Palliative-Geriatric Practice (GPGP) algorithm [50, 51], CEASE algorithm [52], and the ERASE approach [53].

For optimal patient care and to ensure continuity of care, all healthcare providers involved in a patient’s care must collaborate and align their treatment plans [33, 54]. Any modifications to a person’s medication regimen, whether prescribing or deprescribing, should be communicated to other relevant healthcare providers involved in a patient’s care with sufficient information to enable other healthcare providers to deliver the best possible care to their mutual patient. Poor communication and/or information sharing between healthcare professionals have been reported as an important barrier to deprescribing medicines [55]. Collaboration and effective communication among healthcare professionals involved in a person’s care are essential to maintain a unified, person-centred approach and preventing medication misadventure. Prescribers should also document any discussions with other healthcare providers about the prescribing and deprescribing process. This documentation should be detailed and include the rationale for any changes in regimen, the agreed-upon approach for withdrawing medicines (e.g. dose tapering or sequencing of withdrawal), the monitoring plan, and any previous deprescribing attempts.

Ensuring the safe and effective use of medicines is a shared responsibility across the healthcare team. Pharmacists, general practitioners (GPs), and nurses, as members of the multidisciplinary team, are well-placed to assess polypharmacy and help minimise the risk of medicine-related harm [56]. GPs often have longstanding relationships with their patients and understand the broader context in which medicines are prescribed. They play a key role in coordinating comprehensive, continuous care across a wide range of health conditions. In the context of medicine optimisation, GPs can initiate the process for a comprehensive medication review by referring patients to an accredited or community pharmacist and by providing relevant clinical information to support the review process. Regular systematic and comprehensive review of medication regimen is crucial and particularly important where there has been a significant change in an individual’s health status or medicines use [57]. This process aims to identify, resolve, and prevent medication-related problems, and optimise medicines use, goals which may include deprescribing. Comprehensive medication review includes obtaining and confirming the best possible medication history (e.g. information on adverse drug reactions, medicine allergies), current health status, and prognosis. A medicine optimisation intervention, delivered collaboratively between healthcare professionals, was shown to reduce inappropriate prescribing without causing harm to patients [58].

Pharmacists, as experts in pharmacotherapy, are well placed in this regard to conduct medication review with a structured deprescribing focus [57]. Pharmacist-led recommendations on deprescribing arising from medication review are shown to be acceptable to doctors and can have a significant impact on the number of inappropriate medications taken by older people [59]. Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) and Residential Medication Management Reviews (RMMRs) are two types of medication review services funded by the Australian Government [57]. They are conducted by an accredited pharmacist in consultation with the patient and collaboration with a medical practitioner. Additionally, a community pharmacist can deliver a MedsCheck service by reviewing the patient’s understanding of their medications, addressing any concerns the patient may have, and providing guidance on the optimal use and storage of their medicines [57]. Pharmacists embedded in various practice settings, including embedded in general practice, residential aged care services and Aboriginal health services, may also conduct comprehensive medication management reviews as part of their role in the daily practice. Pharmacists play a key role in deprescribing by identifying potentially inappropriate medicines and working collaboratively with prescribers to safely reduce or discontinue them using appropriate methods. Once changes are agreed upon with the patient and their medical practitioner, pharmacists can support implementation by providing tailored recommendations and ensuring the updated regimen is clearly communicated. This may include promptly updating dose administration aids (DAAs) or offering clear instructions for patients who self-manage their medications.

Nurses, including nurse practitioners, registered nurses, and enrolled nurses, play a vital role in deprescribing. Their regular and close contact with patients enables them to detect side effects, monitor symptoms, and contribute meaningfully to medicine-related decisions. Nurses are well placed to identify potentially inappropriate medicines and actively support the planning, implementation, and monitoring of deprescribing efforts [60].

Other healthcare professionals, such as dentists, dental practitioners, and allied health providers (e.g. physiotherapists, podiatrists, optometrists, and occupational therapists), also contribute to interdisciplinary deprescribing. Through routine care and patient interactions, they may observe signs of potentially inappropriate polypharmacy, adverse effects, or medicine-related risks. In these instances, they can raise concerns and prompt medication review by a medical practitioner or pharmacist.

A critical attribute of deprescribing is person-centred care [61]. Person-centred care involves meeting the multidimensional needs and preferences of older people dependent on care, by considering the needs, goals, and abilities of the person as well as, their carers as well as theirand families [62-64]. In the context of deprescribing, person-centred care must take into account an individual's goals, values, and preferences along with research evidence, cost-effectiveness, and value-based care in the decision-making process [65, 66]. For older people who are receiving care from family members and/or formal or informal carers, the views and preferences of their families and/or carers are a part of the key aspects of person-centred care. The implementation of person-centred care can help to identify and contribute to meeting the needs of the family and/or carers of older people [67].

Values and preferences may differ substantially among people. Therefore, the decision to deprescribe should be personalised. Deprescribing should be a shared, collaborative decision-making process between individuals and healthcare providers involving the following steps [68]:

- Creating awareness that options exist, and a decision can be made

- Discussing the options and their potential benefits and harms

- Exploring preferences for (attributes of) different options

- Making the decision together with the person, their families, and/or carers

The decision to deprescribe appeared to be influenced by communication skills (e.g. risk, uncertainty, prognosis communication) [68, 69], the perceived experience of the healthcare provider [65], and a trusting relationship between the individual and the healthcare provider [70]. Treatment plans, including decisions to deprescribe, should be revisited periodically to adapt to the individual's changing needs and preferences [70]. The process should emphasise open communication, respect for the individual's autonomy, and shared responsibility in decision-making.

People living with disabilities may require assistance to exercise their legal rights in decisions that affect their lives [71]. Two key models of decision-making are commonly recognised: supported decision-making and substitute decision-making. These two models should be clearly distinguished. Substitute decision-making involves a legally appointed person making decisions for a person who can no longer make and/or communicate decisions on their own or with support [70]. In contrast, a supported decision-making approach enables an individual to make and/or communicate decisions about their own lives, with the appropriate level of assistance [72]. The principles emphasise that all individuals, with appropriate support, can make informed decisions about all aspects of their lives [73]. Support may take various forms, as outlined by the Australian Government, including the Law Reform Commission [70]:

- Communicating effectively by providing information in accessible and inclusive formats, and ensuring the person can express their decisions;

- Taking time to understand the person's values, preferences, and wishes;

- Drawing on informal support relationships within their social network;

- Establishing formal agreements or appointments to acknowledge support relationships; and

- Creating statutory support relationships through legal appointments.

Both supported and substitute decision-making frameworks are crucial to ensuring shared decision-making and informed consent regarding treatment options. Information and advice must be provided in formats that are inclusive and accessible, such as plain language, visual aids, or assistive technologies, to meet individual unique communication needs [74]. It is also important to recognise that decision-making capacity can fluctuate over time and may vary depending on the context or nature of the decision. Accordingly, the provision of information must be tailored and adapted to the person's specific needs at that time [75].

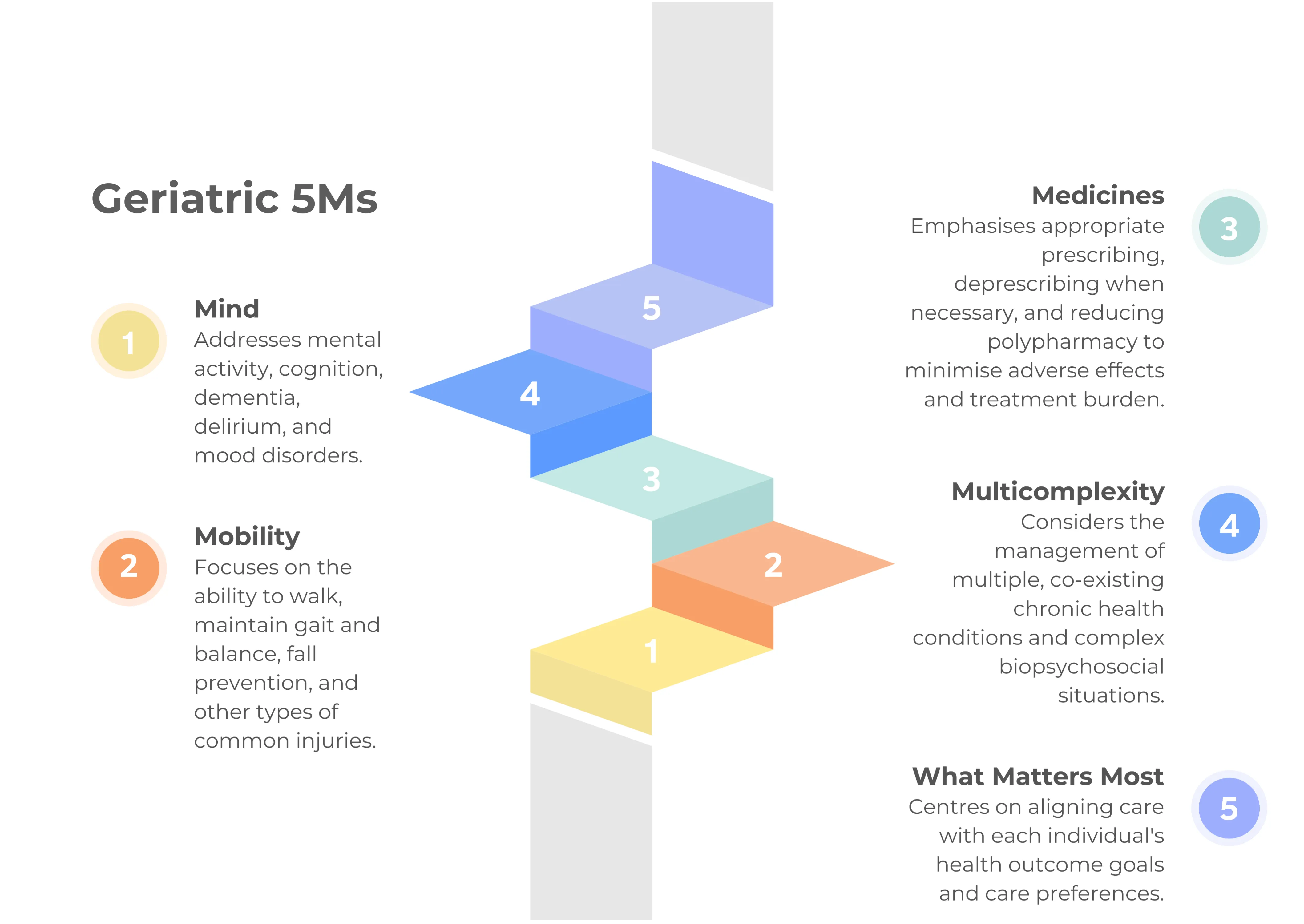

In 2017, specialists in geriatric medicine introduced the five key domains to optimise care for older people, known as the 5Ms (see Figure 2). This communication framework [76] aligns well with deprescribing efforts, emphasising a holistic approach to managing medicines while considering broader aspects.

Through a person-centred approach to deprescribing, previously unrecognised health priorities and concerns may emerge. In some cases, this process may lead to the initiation of new medicines that offer potential benefits while discontinuing others that are no longer necessary.

Figure 2. The 5Ms framework (Mind, Mobility, Medicines, Multicomplexity, and what Matters most)

Older people are not a single, homogeneous group; they represent a diverse population. Some communities face increased health risks as a consequence of various extrinsic factors, including social disadvantages or barriers to healthcare access. Social determinants of health equity are important considerations for healthcare professionals when implementing deprescribing interventions. Older people affected by the inappropriate use of medications are likely to derive substantial benefits in terms of health equity from deprescribing. By reducing medication burdens, lowering costs, and simplifying medicine regimens, deprescribing may enhance access to care and improve health outcomes for this vulnerable population. However, ensuring equitable implementation and addressing potential challenges faced by people with varying health literacy and access disparities is crucial to maximising these benefits.

Disproportionately affected populations such as LGBTIQA+ communities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people with a culturally and linguistically diverse background, as well as people living in rural and remote areas, often face systemic barriers to care and require additional support, considerations, and the use of reasonable adjustments by health professionals during deprescribing. Older people living in rural and remote areas often face geographic, structural, and service-related barriers that can limit their access to healthcare and aged care supports. Key challenges include limited availability of local services, workforce shortages, transportation difficulties, and reduced access to specialised care. Digital connectivity issues may further impact their ability to access information or engage with telehealth and other remote services. Deprescribing approaches can vary significantly depending on the location and setting (whether the person is in a hospital, at home, or in a residential aged care facility). They vary in terms of monitoring capabilities, level of supervision, access to healthcare professionals, and available support systems, all of which can influence the safety and feasibility of deprescribing.

LGBTIQA+ communities comprise individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning, asexual and other who express diversity in gender, sex, or sexuality. Each group, and the individuals within them, has unique lived experiences, historical contexts, and specific needs. In particular, older LGBTIQA+ people may have endured extended periods of societal stigma, discrimination, and, in some cases, criminalisation of homosexuality. In recent years, considerable progress has been made in recognising and addressing the health and wellbeing needs of older LGBTIQA+ people. The enhanced Aged Care Quality Standards underscore the importance of acknowledging and respecting the sexual orientation and gender identity of older people. This principle is embedded within Standard 1, Outcome 1.1: Person-Centred Care (Action 1.1.3).

RACGP provides practical guidance for health professionals delivering primary healthcare to engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in a culturally safe and evidence-based approach. The resource particularly relevant to older people includes a best-practice guide to cognitive impairment and dementia care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people attending primary care [77]. Understanding the historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors that influence health outcomes is essential to creating a supportive and effective healthcare environment. For instance, engaging an Aboriginal Health Worker or Aboriginal Liaison Officer within a hospital setting can provide culturally safe care and strengthen connections with patients, enhancing the acceptability and success of deprescribing efforts.

Many older people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds face cultural, structural, and systemic barriers that limit their access to and engagement with health and aged care services. As a result, they are less likely to utilise supports that promote healthy ageing. Contributing factors include limited awareness of available services, difficulties navigating complex systems, language barriers, and a lack of providers who offer culturally and linguistically appropriate care.

The Australian Government Department of Health developed action plans to address specific barriers and challenges affecting the ability to access mainstream and flexible aged care services. These action plans serve as a key resource for aged care providers [78-80]. The six core consumer outcomes across the three action plans that encourage inclusive and respectful care for disproportionately affected older people and the relevant contexts based on the group include:

- Making informed choices

- Adopting systemic approaches to planning and implementation

- Accessible care and support

- A proactive and flexible aged care system

- Respectful and inclusive services

- Meeting the needs of the most vulnerable

The prescribing competencies framework currently exists, which describes the competencies required for healthcare professionals to prescribe medicines judiciously, appropriately, safely, and effectively [81]. Reviewing the outcomes of treatment is one of the key prescribing competency areas which and includes stopping or modifying existing medicines and other treatments where appropriate. In addition to healthcare professionals often expressing low confidence and self-efficacy for deprescribing [82, 83], there is a lack of focus on teaching and assessing deprescribing skills within healthcare curricula in many countries [83]. To address these barriers, specific competencies required for deprescribing are now being proposed as part of the essential curriculum for pre-registration healthcare professionals in their entry-to-practice degree programs [83]. Deprescribing has been described as a key competency in medicine, dentistry, nursing, and pharmacy, that is viewed to beas inextricably linked to prescribing to achieve high-quality healthcare. Farrell et al proposed the following seven deprescribing competencies to be applied by healthcare professionals in collaboration with individuals, their families, and/or carers within an interprofessional care team (see Error! Reference source not found.).

Each of the seven competencies was expanded in detail in the paper, with descriptions of the knowledge and skills required to meet each competency [83]. Integrating this deprescribing competency framework into the education of other allied healthcare professionals (e.g. physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, speech-language pathologists, social workers) is also valuable as they play crucial roles in the holistic care of older people. Allied healthcare professionals can identify situations where deprescribing of a particular medicine may be considered [66].

Deprescribing competencies adapted from Farrell et al, 2023 [1]:

- Conduct a comprehensive medicine history and health condition information (including prognosis and life stage) as well as understand the reason for medicine use and the expectations of the individual, their carers and/or families, their beliefs, values, goals of care and perspectives regarding medicine use and medical conditions

- Interpret relevant information in the context of desired therapeutic outcomes and goals of care according to the individual, their families, and/or carers

- Identify medicines without an indication (condition resolved or unconfirmed), with low or no efficacy, may have more harm than benefits, or are otherwise potentially inappropriate

- Assess the deprescribing potential of each medicine by weighing the benefits and harms of continuation versus discontinuation of each medicine

- Decide whether deprescribing a medicine is appropriate using shared decision-making with individuals, their families, and/or carers, and the healthcare team (e.g. explore their preferences, socio-demographic backgrounds, capacity in making informed medicine decisions such as health literacy, expectations for medicines, debunk misconceptions and/or explain why medicines may no longer be needed)

- Design, document, and share a deprescribing and monitoring plan for deprescribing (including rationale and process) with an interprofessional care team, individuals, their families and/or carers (lay language) as appropriate

- Monitor progress and provide support to individuals (including rounds of reviewing or making continuous adjustments to the treatment plan as needed)

Deprescribing in practice is challenging as it involves complex considerations in a fast-paced environment (some settings may be resource-poor), taking a person-centred approach that understands the individual's preferences in a particular situation, and coordinating care with multiple prescribers [85]. Drug class-specific deprescribing guidelines and algorithms are available to guide the process, such as those developed by Primary Health Tasmania and the New South Wales Therapeutic Advisory Group in Australia as well as the Bruyère Research Institute in Canada [86-88]. Evidence-based deprescribing clinical practice guidelines developed using a rigorous process exist for a number of drug classes, including cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine [89], opioid analgesics [90], benzodiazepine receptor agonists [91], proton-pump inhibitors [92], diabetes medicines [93], and antipsychotics [94]. The systematic approach for developing class-specific deprescribing guidelines has previously been published [95, 96]. Expert guidance on deprescribing antidepressants, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and Z-drugs is also available [97].

Medicine management is often complex, with barriers existing for both prescribing and deprescribing. The absence of robust evidence in certain clinical scenarios can be a key challenge in practice to guide decision-making. Additionally, barriers specific to the application of deprescribing guidelines in clinical practice include time constraints and competing priorities during a consultation [98]. When a person is prescribed multiple medicines, it becomes increasingly challenging for healthcare providers to approach deprescribing, as existing drug-specific guidelines may lack guidance on how to manage the deprescribing of multiple medicines holistically. The complexity of discussing and implementing deprescribing for people with multiple morbidities and an increased risk of poor communication between parties involved in an individual's care have been cited in the literature [99]. Patients’ attitudes toward deprescribing may also vary considerably between individuals, ranging from positive to negative or simply indifferent [100]. When prescribing is directly influenced by individual requests for specific medicines, the resulting resistance or refusal to deprescribe medicines may also be a barrier to medicine cessation [101]. In addition, some patients may have difficulty in expressing opinions due to reticence toward the healthcare professionals [100] and others may feel uneasy about deprescribing medicines prescribed by another healthcare professional, which may be a kind of loyalty or faith to this person [102]. Similarly, physicians may be reluctant to deprescribe medicines prescribed by another healthcare professional or specialist due to concerns about undermining another practitioner’s treatment plan [103]. For healthcare professionals, deprescribing is associated with major concerns about undertreatment, underdosing, and not complying with the recommendations from existing treatment guidelines, particularly in the absence of clear and consistent high-quality evidence for deprescribing [104].

The current guideline provides healthcare professionals with broad guidance for how to deprescribe that does not replace clinical judgment or the responsibility to make decisions tailored to the individual’s circumstances, in consultation with the person, their family, and/or carers.

The development of this guideline has identified several key areas for future research to support the ongoing effort to ensure the safe and appropriate use of medicines. In particular:

- 1. Understanding patient values and preferences: Further research is needed to explore how patients weigh the risks and benefits of changing or stopping medications. A deeper understanding of individual trade-offs will help inform future recommendations and enhance shared decision-making tools (see Dissemination and Implementation Plan).

- 2. Implementation and practice translation: A consistent theme in the public consultation feedback was the need for continued research and engagement to support real-world application of the guideline. Future efforts will focus on evaluating and strengthening implementation strategies, addressing barriers, and promoting sustainable practice change (see Dissemination and Implementation Plan).

These priorities will help guide future updates and support the broader goal of person-centred care.